Immigrants Seek Stability of U.S.

Citizenship But Cost Is Often a Barrier

AUTHOR | Farida Jhabvala Romero | Published on Apr 12

Guatemalan immigrant Elida Oxlaj and two dozen other adult students hunched over thick U.S. history books at a weekly class in Redwood City, preparing for a test they must pass to become U.S. citizens. Since President Trump took office, Oxlaj has felt an urgency to naturalize, fearing that her green card is no longer a guarantee of safety with the administration’s hard-line immigration policies.

“So far, nothing bad has happened close to my family. But I am still nervous,” said Oxlaj, adding that other legal permanent residents she knows share that concern. “The worst fear is that they’ll kick us out of the country.”

But Oxlaj, who has lived in this country for 10 years, has delayed submitting her application for citizenship to the federal government. She said can’t afford the $725 filing costs on her modest income as a janitor.

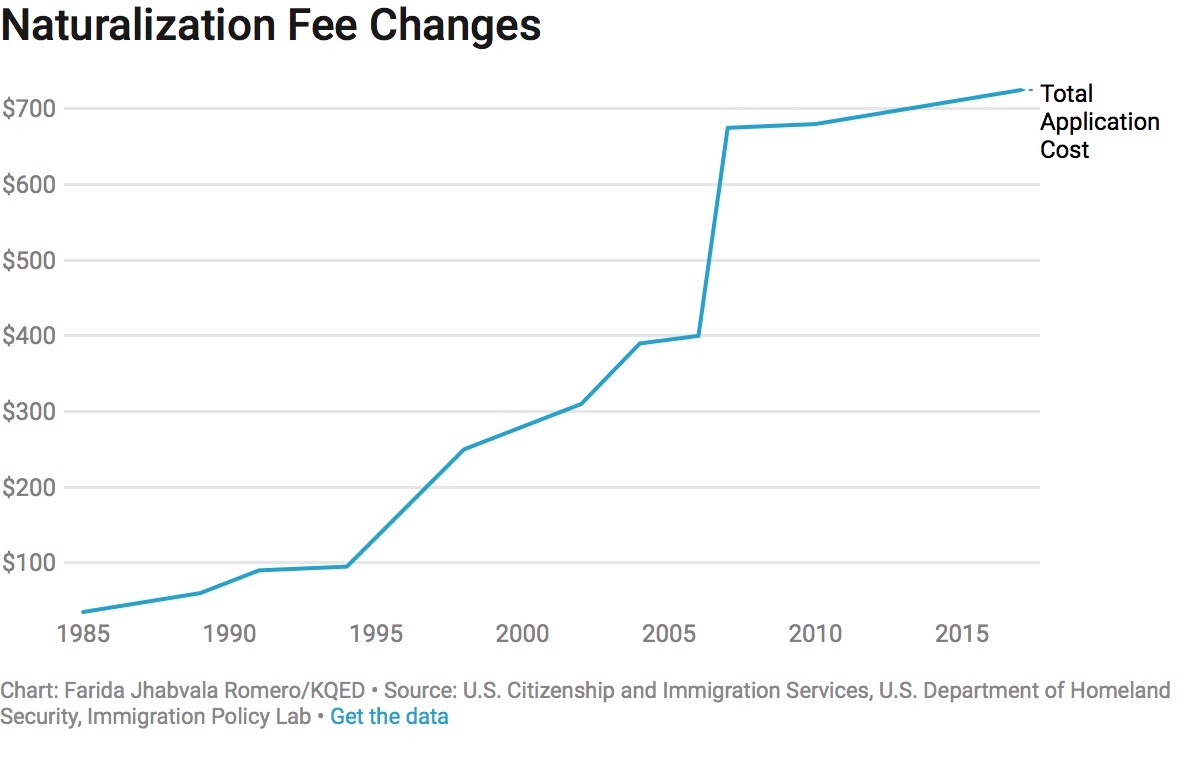

Immigrants are showing greater interest in securing the benefits of U.S. citizenship, including the right to vote and economic advantages, such as better job prospects. But experts warn the steep application fee, which has tripled over the last two decades, is a big barrier for many of the nearly 9 million adults eligible for citizenship nationwide. They say state and local communities are also losing out on additional tax revenue and more civic engagement.

Representatives at the International Institute of the Bay Area, a nonprofit group that offers the free English and citizenship classes Oxlaj attends, said their organization and others nationwide are seeing more immigrants interested in naturalizing since the 2016 presidential campaign.

“Many of our learners were perfectly happy to be permanent residents,” said Sam Bianco, a class coordinator with the International Institute. “But the current climate in the immigrant community is very tense and fearful, and the only way to have the security of being able to live the rest of your life in the United States is through obtaining citizenship.”

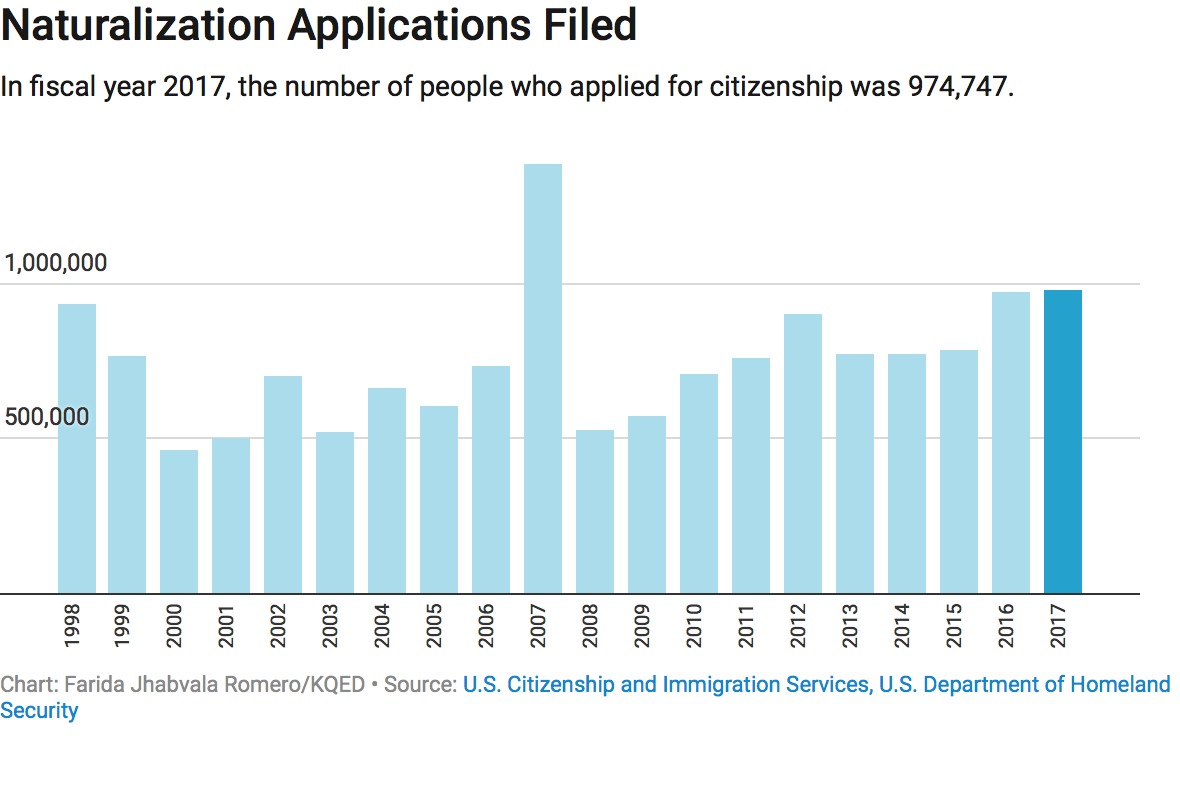

In fiscal year 2017, more people applied for citizenship than in any year but one in the last two decades, according to figures from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. The only exception was fiscal year 2007, when applications surged, largely in anticipation of a significant fee hike scheduled for later that year.

Most of the permanent residents the International Institute serves are from Central America and work in blue-collar jobs in the service and construction industries. Bianco said many students delay applying because they can’t come up with the money to pay for the fees. Immigrants may also struggle with limited English or lack information on the process.

Most of the permanent residents the International Institute serves are from Central America and work in blue-collar jobs in the service and construction industries. Bianco said many students delay applying because they can’t come up with the money to pay for the fees. Immigrants may also struggle with limited English or lack information on the process.

The total cost of applying for citizenship has increased dramatically over the last 30 years. The price tag was only $35 in 1988 (about $80 in today’s dollars).

Researchers say low-income workers have less disposable income for the fee in regions where the cost of living is high, such as the San Francisco Bay Area. Oxlaj, a mom of two, has been trying for months to save enough money for the citizenship application, she said.

“More than $700 is just too much,” said Oxlaj, who recently became the sole breadwinner for her family after her husband was injured. “We need that money to pay rent and other bills.”

Why Does It Cost $725?

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, oversees lawful migration. In contrast to many other government agencies that are funded through appropriations of taxpayer money, USCIS relies on application fees to pay for more than 90 percent of its operations. That includes employee salaries and computer software.

“Congress took a look at the fact that there is a cost to processing these immigration applications and they said, ‘Who should pay the cost, the taxpayer or those who are applying for the benefits?’ ” said Sharon Rummery, a spokeswoman with the agency. “They decided it’s the applicants who should pay.”

Every two years, USCIS conducts an audit to ensure that fees are sufficient to cover expenses. Rummery said one reason the agency charges more now is because of additional national security screenings. The current citizenship application is 20 pages long, but in 2013 it was only 10 pages.

Agency Offers Discount

USCIS offers to waive the citizenship application fee completely for extremely low-income immigrants who can prove they earn less than 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines (an annual income of $37,650 for a family of four). In 2016, at the end of the Obama administration, the agency announced it would also offer a substantial fee cut for immigrants who earn up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

This is the kind of information that potential applicants can find at citizenship events organized regularly by nonprofits and cities. Online tools are also available to help people figure out if they qualify.

But those who could benefit from the reduced-cost option often don’t know about it, said Duncan Lawrence, who directs the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford University.

“We know there are actually lots of people who are unaware of the federal fee waiver program and so they may never in the first place apply for citizenship because they think that it costs $725,” said Lawrence.

And for those who make a bit too much to qualify for the agency’s discount, the price of petitioning citizenship “can be a huge barrier,” said Lawrence. He estimates that about 400,000 lawful permanent residents in California could fit that description. The state has more than 2 million adults eligible to naturalize.

Lawrence wanted to know how big of an obstacle the cost of applying really is. He led a study, published in January, that followed about 860 low-income immigrants living in New York City who earn just a little more than the cutoff for the USCIS fee discount. Some got vouchers from New York State to cover their citizenship application, while another group didn’t.

Lawrence found that financial aid made a tremendous difference: People were nearly twice as likely to apply for naturalization. He said other local governments may want to follow New York’s lead.

“For local communities and states, there’s an opportunity, based on what we’ve demonstrated, to help this low-income group overcome the financial challenges,” said Lawrence.

‘It’s Important Cities Step Up’

In California, home to about one-quarter of all U.S. adults eligible to naturalize, some cities have started making a modest investment.

San Jose used a grant to cover the citizenship application fee for about 50 immigrants who finished a financial literacy course last year. The city is planning a similar program this year.

In San Francisco, the fear in immigrant communities after the 2016 presidential election motivated city leaders to allocate about $90,000 to pay half of the citizenship fee, said Rich Whipple, deputy director at the San Francisco Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs.

“It’s important that cities step up to help people calm those fears, and I think that helping to cover the fee is part of that,” said Whipple, adding that over 100 immigrants who live, work or study in San Francisco have benefited so far.

Several nonprofits in California help people fill out their citizenship applications, but few finance the fee. One of them is Mission Asset Fund, a financial services organization in San Francisco, which provides zero-interest loans statewide, said Mohan Kanungo, director of programs at the organization.

‘It Would Change The Country’

Immigrants who naturalize can benefit from a greater sense of security and are more likely to have higher incomes and own their homes, compared to people who don’t get citizenship, according to researchers.

If half of the eligible immigrants in California naturalized, they would earn a combined $18 billion more over 10 years, according to a 2016 report by the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at the University of Southern California.

State and local communities stand to gain tax revenue when immigrants earn more, and they also benefit from increased political participation, which would be a boon for American democracy, said Melissa Rodgers, who directs a national coalition of nonprofits called the New Americans Campaign.

“It would change the country,” said Rodgers. “It makes an incredible difference when people become eligible to vote, to express their core beliefs and to engage in our democracy.”

To be eligible for U.S. citizenship, lawful permanent residents must have a record of good moral character and have lived in the country for at least five years. The residency requirement is three years for green card holders who are married to U.S. citizens, like Elida Oxlaj, the citizenship student.

Because of her income, Oxlaj might qualify for a federal fee discount, but she didn’t know it was a possibility.

“I’m going to investigate what I have to do so I don’t have to pay so much. and I can finally send my application in,” she said.

COPYRIGHT © 2018 KQED INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. | TERMS OF SERVICE | PRIVACY POLICY | CONTACT US